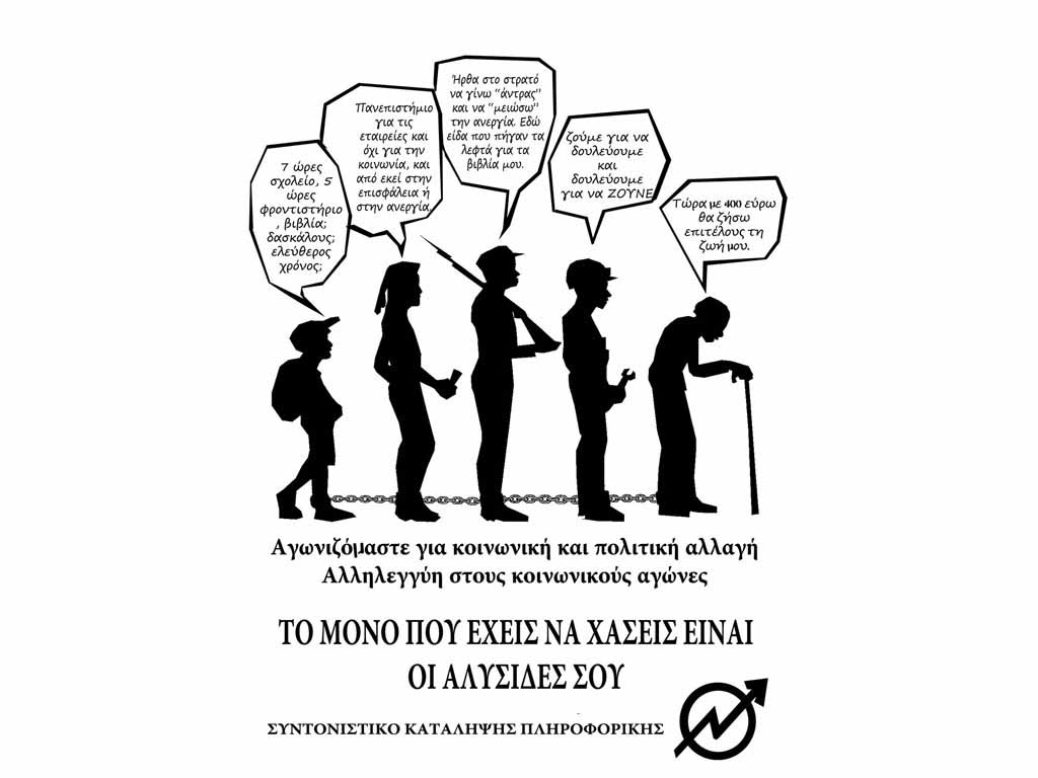

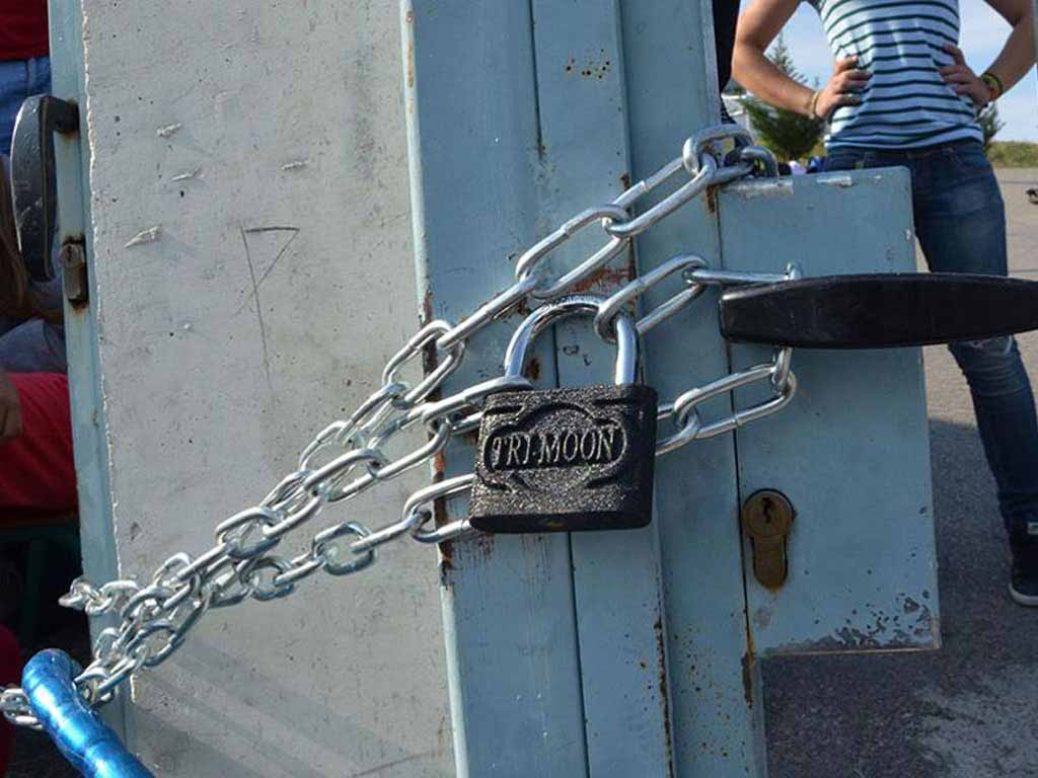

The squats of public buildings (workplace, school units, abandoned buildings) constitute a form of social struggle, whose aim is putting pressure on the State or a certain employer towards the accomplishment of a worker- or people-friendly target. At least, this is what history, political science, sociology and dictionaries tell us.

In Greece after the military junta, the momentum of the Athens Polytechnic uprising (November 1973) pushed towards the consolidating of a culture of almost annual squats “traditionally” – at least when it came to schools of the secondary level (gymnasiums – lyceums).

The peak of a good excuse for such demonstrations of revolutionary gymnastics were the reformatory attempts of the first Mitsotakis government (1990-91), when the Minister of Education was Vassilis Kontogiannopoulos. The protagonist of squats was the president of the 15-member student council of the Ampelokipoi Multidisciplinary Lyceum. And who was that? But none other than current Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, who, as you may recall, had been interviewed on the issue by Anna Panagiotarea on Mega Channel (the degree of randomness of the incident is left to the readers’ judgement).

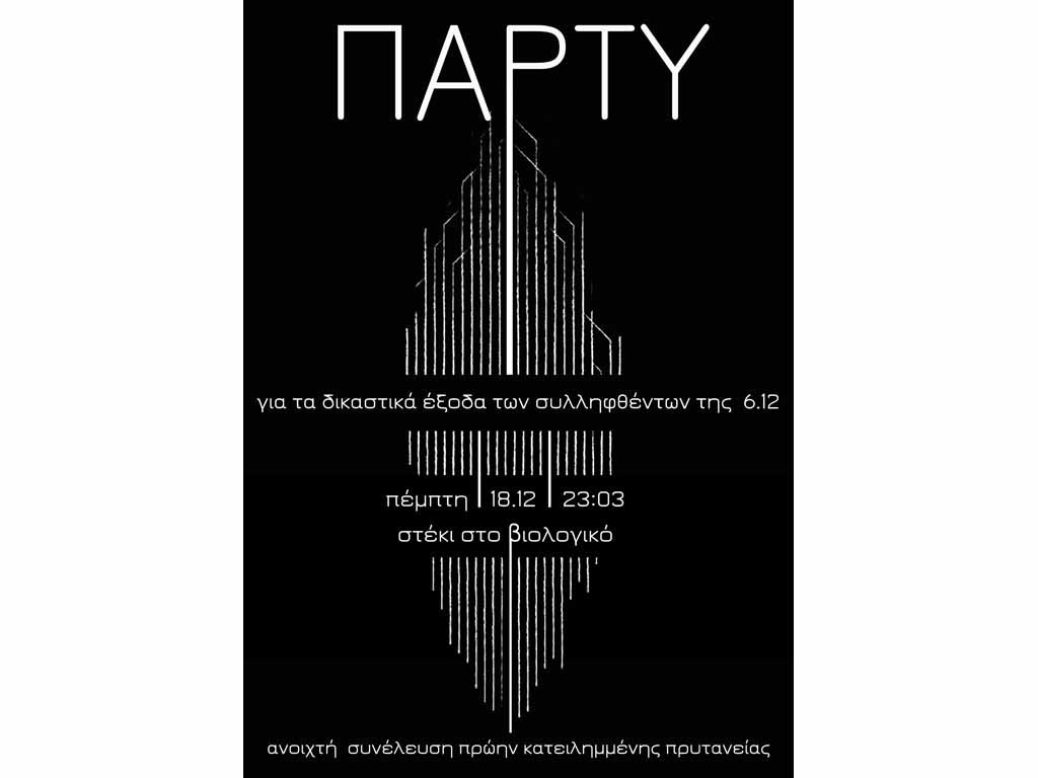

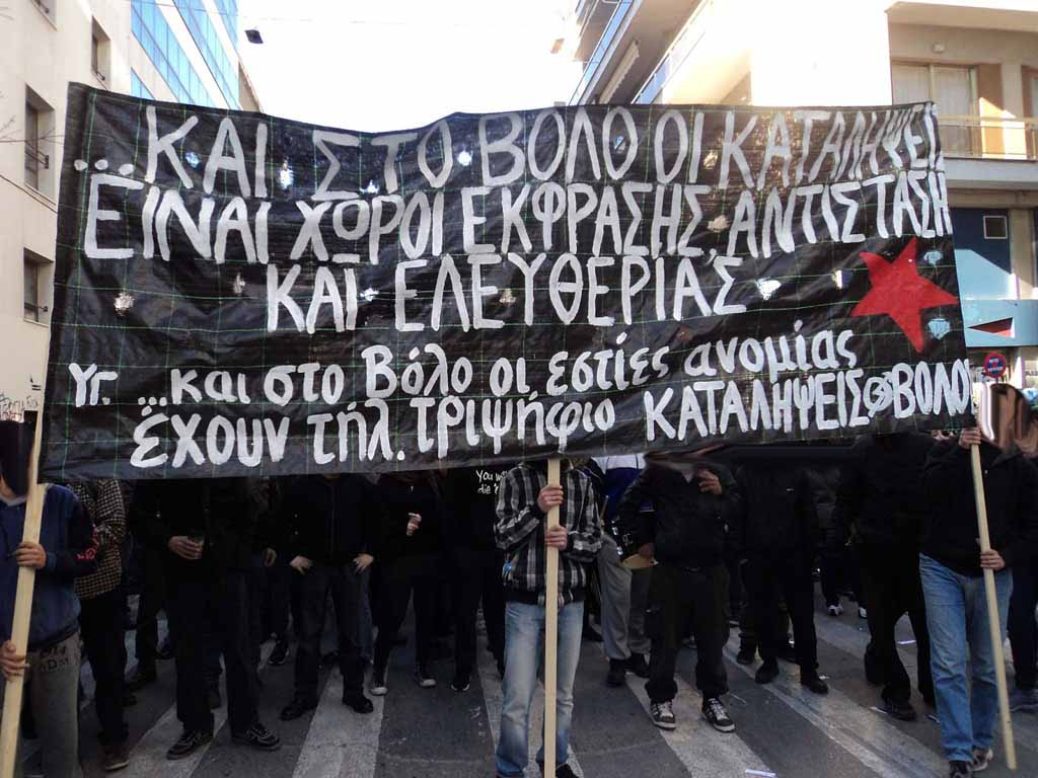

Despite the fact that the squat of a building (usually called “Villa”, like Villa Varvara) by a group of anarchists may be characterized as a consistent ideological struggle with, at times, ingenious slogans, it is mostly the squats of schools that have been imprinted on collective memory; for customary reasons, they are seasonal (come October, like pomegranates) and equally ingenious in demands.

Looking back at some of these demands, let us remember the following:

- Cleaner toilets.

- More excursions.

- Cheese-pie with feta (instead of semolina or white cheese) at the canteen.

- Advancement of all students who didn’t pass the exams to the next grade.

- Longer breaks.

- Five-day trip to Italy.

- Softballs for gymnastics.

- Support of the next school.

In the university context, squats were more ideologically charged (fatally of the left disposition) and were focusing on the annual reformations of each Minister (the peak was in the 2004-07 period, during which the squat movement emphasized on reacting to the re-examination of Article 16 of the Constitution about “free” education). The reformations of that period, as they were included in the relevant legislation passed by Marietta Giannakou-Koutsikou, gave, among other things, the coup de grâce to University Asylum, as it had been established after the military junta.

What was the Asylum? It was the protection of function and research conducted in Universities by the intervention of oppressive mechanisms of the State (Police, Army). The logic behind its establishment was to avoid possible future repetitions of the indiscriminate intervention of the military junta (1967-74) in the universities. This intervention reached its peak with the appointment of a so-called student councils leadership, along with the, necessary for the maintenance of the junta, censorship.

The forces of PASOK and the Leftist parties defended the maintenance of University Asylum throughout the Metapolitefsi (the period after the collapse of the junta). The urban Right (New Democracy), on the other hand, piously desired its abolition, since its governments (1974-81, 1990-93, 2004-09) suffered by far most of the squats (despite the famous “lay back, Gerasimos” that was directed at Minister Arsenis, during the 1998-2000 PASOK government). The political prerequisites for such an abolition did not bear fruit until 2004; that was when Kostas Karamanlis managed to win the sole easy victory of ND in the Metapolitefsi. It was because of that victory that the Prime Minister sensed he had the comfort to win the historic revanche from the powers of “blind violence and anarchy” that were active in the Universities. The average “family person” shows distrust not only towards squats but to almost all forms of social struggle. Conservative by nature and addicted (by DNA almost) to mediation as the only acceptable way in which urban democracy can function as a regime, they despise initiative and youthful spontaneity – whether it concerns opposition to the abolition of free education or the misunderstood demand about cheese pie with feta (which may just as well have contributed to the protection of indigenous production from the onerous effects of Common Agricultural Policy that the EU had imposed). Where other people see struggle, they see “anarchy” (both Kropotkin and Bakunin are turning in their graves).

However, the gradually acquired customary character of squats, as well as the inability to de-crystallize definite demands apart from the classic ones (free education, no to the abolition of asylum, free books, etc.), pushed the “middle ground” of society – the critical mass that, through its tolerance, legalizes any given enforced politics – towards the above mentioned conservative viewpoint. This ideological shift is also reflected in the results of the student elections: in the last 30 years, participation is well under 50%; DAP-NDFK (the ΝD line-up) is by far the one to gather most votes every year and the only relatively interesting development lately was the rise of PKS (the KKE line-up) to the 2nd position as a consequence of the inability of DARAS (the SYRIZA line-up) to benefit from the detriment of PASP (the PASOK line-up). Moreover, the disdain of the communicating vessel of the wider trade union movement had further dissolving effect to the student movement – this phenomenon will be analyzed in another article.

Are there no more reasons for social struggle? Not in the least – we need only look around us. How can any struggle win society over, in order to succeed not only in legalizing itself in people’s conscience but in achieving its goals as well? With sobriety, consistence and clear targets. Even the demand for a 5-day trip abroad can be founded with dignity; if, for instance, it is placed in the context of a visiting program to cultural sights, with the undertaking of a relevant project/research. On the University level, the re-establishment of asylum on its initial foundations requires vigilance and guarding of struggles by the students: both as far as the actual security of university buildings is concerned and regarding the consistence of the context in which demands are made. Otherwise, the broken desks will be forever dominant (in terms of media) over the request for free books – even with a “Leftist” government in power.

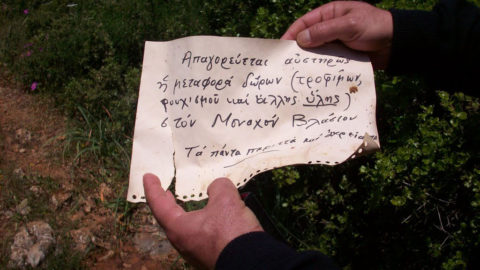

In specific, the current government’s management of the recent squat in Schools of the National and Capodistrian University of Athens suggests, if nothing else, an ambiguity between its major ideological label and the need to maintain the existing legal context. The ambiguity in question is demonstrated even more intensely by the phenomena of squats in the SYRIZA central offices – or even the Parliament’s colonnade by groups of anarchists. The feasible and dignified way out for a power that wants to be called consistent with its own principles is none other than the re-defining of legal context and its unswerving application. As Costas Laliotis used to say: “There are no dead ends in democracy.”

current_Panos