October 31st is internationally celebrated as Savings Day, in memory of the founding of the International Postbank Institute in Milan, on 31 October 1924.

In the past, on that particular day, “The Virtues of Saving” was the most popular essay topic in schools, so that students would be accustomed to the notion and – perhaps – condition themselves to its advantages.

Let us, then, look at the historical course of saving, as well as its meaning today in Greece – as it runs its sixth year of ongoing financial crisis.

Hesiod was the first to praise the benefits of saving with the following phrase: “Ει γαρ κεν σμικρόν κατά σμικρόν καταθείο, και θαμά τούτ΄ έρδοις, μέγα και το γένοιτο“. The meaning is: If you save little by little and do this continuously, you will succeed greatly.

The keeping and storing of money and/or goods in times of surplus is present in almost all human societies; the aim is mostly the meeting of respective needs in more difficult times.

And we say in almost all societies because, when capitalism first appeared as a threat to feudalism (18th century), some people opined that saving presented an obstacle in the way of greater economic growth. Characteristic supporter of this opinion was Bernard de Mandeville, who sang a praise to extravagant expenses in his book The Fable of the Bees (1714); and also Montesquieu with his famous quote: “If the rich do not spend a lot, the poor will starve to death“. In retrospect, it is easy to deduce that these particular views were nothing more than the dying breaths of a socio-economic system that was collapsing to give way to a new organization of society.

In the first decades of capitalism, saving constituted a sine qua non term for the economy’s growth, since the amounts saved in the banking system were immediately used in investments, in order for the capital’s productive capacities to expand. This perception was also “dressed up” in terms of an ethical construct: this was nothing more than the so-called Protestant ethics – the spirit of parsimonious living of “family men and women”, who work tirelessly, consume modestly and save prudently; both for the possibility of difficult times that may strike commerce and for the (until such times come) benefit of society as a whole from accumulated wealth, which can be put to further good use.

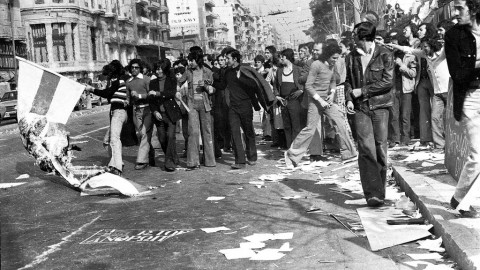

Looking at the historical evolution of capitalism, saving decreased at the beginning of the 20th century when the average profit percentage dropped; this happened due to the intense antagonism between the Great Powers of the time when they were dividing the world among themselves. World War I and the opportunities of reconstruction that presented after its end were accompanied by a tendency of resource wasting, with an emphasis of financial institutions (businesses, natural persons) on thoughtless consumerism. The blooming of the Stock Market helped significantly in this respect, since it led to the digression of whatever transactions were taking place there from businesses’ search for capital expansion (the money market’s initial reason of existence) into pure financial speculation.

All this is, more or less, what led to the Stock Market Crash of 1929, the Great Depression of the 1930s, the rise to power of absolutist regimes and the increase of state intervention into the economy; the latter’s aim being that savings would prudently be turned into public investment so that jobs would be created and the steam engine of growth would be restarted.

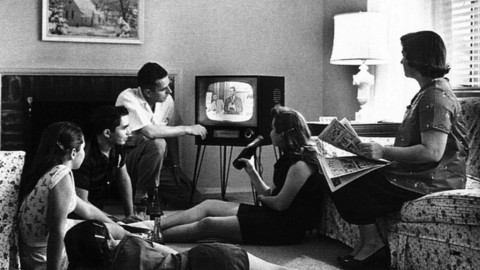

The intervention of World War II (1939-1945) merely encouraged co-operation and good measure as a way of thinking to be incorporated in the subjects’ financial activity. However, the great blooming of the following decades (the baby boomers’ generation), when all households were gradually equipped with a television, a car and a refrigerator, led the financial cycle into yet another spectacular rise.

The great oil crises at the end of the 1960s and 1970s did not intercept consumption as a percentage of the available income; therefore, they did little to encourage saving. Technological advances made in the following decades gave people access to a series of particularly attractive technological consumerist goods (as discussed in “My precious smartphone” and “More mobiles, less communication”); the outcome was that saving was, from the 1990s onward, a graphic luxury – a remnant of other times. Modern consumerist society wants people to be easily satisfied, demanding, uneasy, tireless viewers of consumerist evolution – in short, every one of us is a “consumer king”. It was at this precise moment that the first memorandum appeared…

It is too early to write a eulogy for savings. It may be that the entry of Greece into the European Monetary Union was accompanied by the wiping out of deposits’ interest rates (while, at the same time, the interest rates of loans remained at significantly higher levels than those of the official inflation rates), yet it is never too late for the reclaim of a controlled savings culture as part of a less reckless attitude to life; one that will, in the future, shield us from the national depression of yet another financial crisis.

Every financial institution (be it a business or a natural person) that respects itself should secure the conditions of its finances’ long-term viability – which, in extent, will secure its own very existence. However, for better or worse, this passes inexorably right through the restricting of consumption as a percentage of available income. It is not necessary for any given income increase to be simultaneously converted into the latest smartphone. The following of consumerism frenzy leads to none other than a constant feeling of teenage dissatisfaction. Fixed as we are to the neurosis of consumerist tendencies dictated by the Marketing Departments of conglomerates, we undermine, both individually and collectively, our dignified long-term existence. And, since the financial crisis is a good excuse for self-critique (because we cannot simply blame everything that happens to us on others), regardless of International Days of commemoration, put something on the side. You might finally experience a novel feeling of security.

current_Panos