The festive season is, without a doubt, the most beautiful and luminous of the whole year! And, despite the common belief that “Christmas is for children”… Ιn reality even us “older” children enjoy it and seek the magic – even though we often say that it’s just a good excuse for rest and good food.

Christmas in the 80s

In modern Greece, Christmas has gone through many fluctuations regarding the way we experience it. Therefore, in the 80s, Christmas customs were very much alive in Athens, and in the province as well, with housewives cooking expertly all the traditional foods and special dishes for the festive table, around which everyone gathered in an atmosphere of affection. And everyone doesn’t just mean the family – even if the family was made up by three generations. Especially in the Greek province, all houses were open to friends and acquaintances; in every table there was a seat reserved for the lonely or less fortunate people: for the neighbor; the old friend; even someone who happened to be passing through the village. It’s not that people were that rich and the food was endless; that was not the case. There was a place on our table because, first and foremost, there was a place in our heart. And when kindness, compassion and love are endless, everything else, as if by magic, is provided!

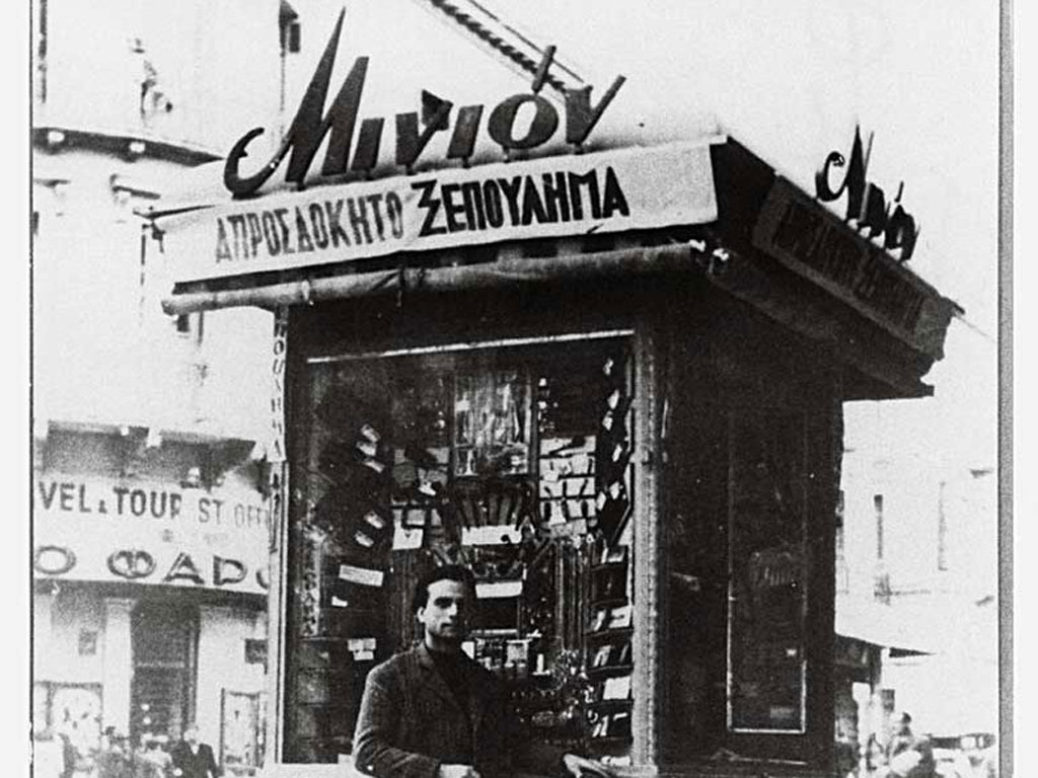

Of course, as you must remember, back then, children still used to run carefree in the streets on the eve of Christmas and New Year’s Eve, little triangles and harmonicas in hand, to sing the Christmas carols and gain pocket money and sweets. And, afterword (if they lived in Athens), they would go for a stroll with grandpa to the legendary Minion Store in Omonoia Square to have their photo taken (with the also legendary Polaroid camera) with Santa Claus and Mary Poppins, both of whom assured all children they would bring them the presents of their dreams come New Years’ Eve. And so the deal with the jolly saint was sealed; having been preceded, of course, by a letter to him, which had been sent with a large amount of piety by post to an always unknown address!

Τhe customary Greek traditions took place – especially in the province – consecutively, not so much in order to impress us but to get us in the right religious mood. It’s true that these holidays lacked the suspense of later years, since their most noisy time was the dawn of the new year: when children got out of bed full of enthusiasm (the way no child ever gets out of bed on a school day) to see if Santa Claus had left them presents under the tree. For the older ones, the presence of presents (apart from the unspeakable joy it offered) constituted a secret reassurance of love and acceptance; something that bears no resemblance whatsoever to today’s counting of likes and shares of our Facebook photo – kourabies in hand! That was indubitably the time of innocence and romanticism! None of us ever wondered how Santa Claus could get in since the house had no chimney; or, if it did, how could he possibly go down the narrow chimney; and, if he did, how could he distribute all these presents in one single night! And we never wondered because, in the end, it didn’t really matter – for children and adults alike! And those of us old to remember those times will agree that the secret of Christmas in the 80s was not luxury and money! Because, back then (pretty much like now), we didn’t have that much money but neither did we have what followed the inflow of money: globalization, consumerism and emptiness. The secret of Christmas back then was simple and grand at the same time and can be described by merely three words: love, simplicity, warmth!

Christmas in the 90s

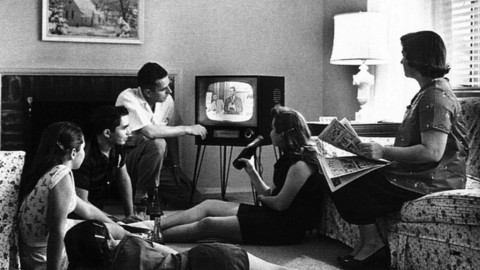

Christmas in the 90s was partly 80s and partly “different”! There was money coming in Greece, we were a bit more modern, we had been acquainted with the Stock Market. We were traditional Greeks, no doubt about that; but with a touch of Europe! The simple yet elaborate decoration of houses and cities started being replaced by the shinning onslaught of ornaments! Endless rows of Christmas lights in the streets and in our homes, the epitome of which was the giant Christmas tree of then Mayor of Athens Avramopoulos that had been proclaimed the biggest and most luminous in all of Europe! But, even so, the memories of the 80s and the years before, were still deep rooted in our hearts and so children still went around singing carols; but they wanted a much more generous tip for their trouble and would frown when given melomakarono or kourabies as a treat, since, back home, mum had bought (probably not made herself, working long hours as she did) a ton of sweets from the bakery. Santa Claus was still around but he was somewhat more “cult” since he was supposed to bring expensive and less useful presents: more toys as opposed to items of “necessity”, such as clothes, shoes and books. As for the grown-ups, they had the perfect excuse to buy the latest technological feature: the mobile phone (the same size as a loaf of bread – black and white screen back then). Not that it was necessary, of course; but as a means of investing their extra cash – something fluctuating between curiosity and a slight (or heavy) case of showing off!

Those Christmas were certainly “paler” but hadn’t yet lost their traditional coloring. And by saying “paler”, I mean that the family still gathered around the festive table but it wasn’t open to all, despite the fact that it had more, sophisticated dishes. However, the gathering didn’t last long – just until dessert. This happened because people’s psychology contained a certain compulsory element of the type “It’s Christmas – festive season and all – let’s all eat together”; yet, what was underlying was everyone’s explicit intention to go about their own scheduled outing with friends after the gathering. The evening parties, veggheras and happenings had already started invading Greek culture – not always for a humanitarian cause! Most typical of all this atmosphere was the big party for the change of the year at Syntagma Square or Kotzia Square. The Christmas hymns that were still sang melodically at the annual school celebrations had acquired a “let’s get it over with so we can go shopping for presents with our godmother/have coffee with friends/have lunch in a fast-food chain” note. There was still love and warmth around; albeit expressed in a modern fashion. But romanticism – no. Romanticism had left us for good.

Millennium X-mas!

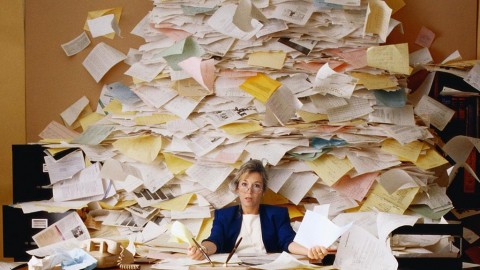

And then… Millennium was upon us! And Santa Claus became a decorated 6-floor multi-store, full of everything you could have imagined! And all of us, convinced that we all needed everything, bought with plastic money whatever the human mind could conceive and, surrealistically, name it “necessary”. Children received so many presents and ate so many sweets that they didn’t really need Santa Claus; and they didn’t roam the streets singing carols because mummy had become a bit phobic to let them run around all day – especially in the big cities with so many cars, such hectic rhythms – and more! Our festive table was full of foreign and strange caloric dishes – that is, when we found the time to gather around it as a family. Because, usually, we were mentally and, most importantly, physically elsewhere. We took rides in luxury cars (usually bought with borrowed money) and made trips to London, Paris and Vienna (also paid with holiday loans)! With Greece in the midst of development for the Olympic Games and the euro succeeding the drachma, we were now legitimate Europeans and loved the title, the luxury and the culture! And, at the same time, forward came the intense rhythms, the millions of lights flashing like strobes, the uncontrollable luxury, the technology, the consumerism, and the emptiness; and the essence of these holidays went out the window. However, all that lasted until 2008: when the average modern Greek started hearing (perhaps) for the first time words and phrases such as financial crisis, global marketing, Goldman Sachs, referendum, emergency taxes, unemployment… That was when we started lacking the abundance of luxury and comfort that characterized the previous years and, on top of that, our adjustment was extremely abrupt and came as a shock!

But no… I will not get into describing what this country is going through for seven consecutive years! At least not in this article; and this is because I just realized that the dreamy character of this article (with an essence of nostalgia from the past, if you will) was immediately side-tracked as soon as I started writing about the Millennium – when my sole intention was to give you a Christmas tour (like the genuine Beauty Guard traveler that I am)! Therefore, I just communicated with the most rationalist of Beauty Guards, current_Panos, to take over! He is possibly the only person (being a financier) who (with his unique sense of humor) can discuss in depth the topic “Christmas in the time of financial crisis” without depressing everyone. So, I will take you back into the past yet again; this time far back into the past to talk to you about something else. Something beautiful, Christmas-related and customarily Greek! I will, therefore, talk to you about our Greek customs: where they come from and how they survived the passing of the years…

Christmas tree or boat?

As far as festive decorations are concerned, Greek Christmas tradition dictates a boat with masts (in the fashion of a sailboat) for the islands and a tree for the mainland. Both these customs trace their roots back in ancient Greece. According to surviving sources, in ancient times, the boat was decorated in honor of the god Dionysus (Bacchus) and symbolized his coming; while the decoration of the tree is connected to the worship of Rhea, goddess of wild nature and all creative powers of the land.

In Christianity, it wasn’t until the 4th century that the 25th of December was established as the day of celebrating Christ’s birth; furthermore, the first time that a Christmas tree (a fir tree, to be exact) was decorated was in the 8th century. In Greece, the Christmas tree resurfaced very recently – in 1833, meaning when King Otto was reigning; but, since it was considered a German custom, Greeks rejected it as imported and went on to decorate their boats. Like the nautical and blue country that is Greece, the decoration of the boat (and nothing but the boat) during the festive season was obligatory for many centuries and, from a certain time onward, this decoration was absolutely identified with the welcoming of seamen to their homes after a journey. Today, of course, the decorated tree is the norm in most areas of Greece with very few exceptions – like that of the island of Chios. To this day, Chios continues to honor its seamen, thus keeping folk traditions alive. Therefore, every year, the custom of decorating boats is revived; on the island, people build various boat replicas, whose size can very well reach 5.5 meters. These boats are then presented at a feast, where one of the participants wins an award for the best boat of the year to come.

On the other hand, in those regions of Greece where the sea is nowhere to be seen and certain villages of Northern Greece in particular, apart from the fir tree, there is still the custom of the so-called Christoksylo (the Christmas log) – connected not so much with traditional decoration but with house warmth. So, every Christmas, the men of each house go to the forest or the fields and cut a very large log (usually from an olive or pine tree) and offer it to the lady of the house, so that it is placed in the fireplace and spread its warmth to the whole house. According to tradition, the log should be big enough to burn throughout the festive days.

Finally, yet another decorating custom of the festive season is the Christmas wreath. This is essentially a wreath made of mistletoe, pine cones and red bows, which is usually hung above the house entrance. It is circular to symbolize eternity; moreover, it is believed that it brings fertility and prosperity to the house. The wreath is sometimes also decorated with candles as a remnant from antiquity to symbolize the sun in winter solstice, while the mistletoe, the pine cones and the red ribbons symbolize summer.

Shall we sing you a Christmas carol?

Triangles and caroling it is, then, all around Greece: being sung by children on the day before Christmas, on New Year’s Day and on the day of Epiphany or Theophany, their words being different according to the feast. The ritual of caroling is known to all Greeks, as we all sang their words during our respective childhood. So, every year, these days, groups of young children roam the streets with their characteristic triangles or sometimes with their harmonicas; they come knocking on our doors and ask “Shall we sing you a Christmas carol?” If the owner of the house is in the mood, he’ll let the children sing and give them pocket money, while the lady of the house will treat them with kourabies, melomakarona, chocolate and diples with honey and nuts! Beautiful imagery: with beautiful children’s faces and voices… all Christmasy and lovely!

However, the Greek word for caroling (κάλαντα) derives from the Latin word calenda, meaning the beginning of the month. But the custom itself comes all the way from ancient Greece, when it was named ειρεσιώνη and it was very similar to today’s tradition. According to surviving ancient texts, children held in their hands boat replicas (symbolizing the coming of Dionysus, as mentioned above); alternatively, they held olive tree or laurel tree branches decorated with red and white threads. They used these threads to tie the presents they were given at the houses they visited with a special knot.

At the end of this article, you will find an Appendix with the words of all three Christmas carols (at least a version of them – there are several in Greece) to get you in the Christmas spirit; also, despite the fact that we have all gone knocking on doors to sing them, we probably don’t know the full version!

The nativity scene, the star of Bethlehem and the three magi bearing gifts

The nativity scene and the star of Bethlehem are two elements of tradition intrinsically connected to the Christmas spirit; and not just in Greece, since they are always present in all the stories related to the birth of Christ. And so, in Greece as well as in other countries, they constitute an integral part of Christmas decoration and celebration.

According to the Gospel of Luke in Christianity, the nativity scene is nothing more than the stable where Jesus Christ was born. Therefore, in remembrance of this scene, we will very often see in the city or village plaza (in various parts of Greece), along with the decorated tree, beautiful nativity scenes that represent the humble stable of Bethlehem. These nativity scenes are rather typical and depict a replica of Jesus Christ as an infant, the Virgin Mary and Joseph, the three magi bearing gifts, little sheep, plenty of straw and all the imagination that went into their designing and decorating. Likewise, in our houses, we tend to place miniature nativity scenes under the tree.

The star of Bethlehem that, according to tradition, shone like no other star lighted the way for the three magi; it served as a guide in their quest to locate the infant Jesus, kneel before him and hail him as the new king of the Jews, bestow upon him godly honors and offer him gifts.

Magi were wise men occupied with natural science and medicine; also with apocryphal knowledge such as prophecies and the interpretation of various phenomena. In general, magi were very important persons since they occupied seats as royal councilors and even took part in military campaigns. We do not have extensive knowledge about the three particular magi related to the birth of Christ; yet, the information provided by Luke in his Gospel – that they arrived from the East – leads to the conclusion that they probably came from Persia, since there was no other country east of Palestine with a tradition in dealing with magic (in the positive meaning attributed to the characterization).

Moreover, according to Syrian myths (which are, however, not verified by Christian tradition), the magi that knelt before Christ were three and their names were Melchior, Balthazar and Caspar. Each of them gave the infant Jesus a special and symbolic gift. Melchior gave him gold, symbolizing the fact that the infant was a true king. Caspar offered frankincense to say that this was not a mere king but God himself. It is common knowledge that, since antiquity, many religions and cultures around the world have attributed to this particular substance the characteristic of divinity. The third one, Balthazar, offered the infant myrrh, which symbolized the very early death of Jesus, since the rubbing of the dead body with the substance was an inseparable part of the burying ritual. In exchange for the gifts they offered, the three magi received a piece of the infant’s swaddling clothes; it was supposed to serve as proof that he had been born and worshiped with honors, in case people didn’t believe them.

Traditional Christmas sweets

I’m sure they don’t need much in the way of introduction: traditional Greek Christmas sweets are by far the tastier and healthier you can have. Let’s look at them briefly:

The Christopsomo (Christmas bread) is made on the day before Christmas, with particular piety and a special type of yeast that is usually mixed with basil leaves. It is a fragrant bread that is presented at the Christmas table, where the owner of the house cuts it and distributes it among family and guests. It is imperative that the Christmas cross is carved on the bread, with other decorations around it. Its symbolism is identical to that of the Holy Communion.

The vasilopita (Basil’s pie) is a special dessert resembling a cake, which is ritualistically cut on New Year’s Eve – either after the change of the year or on the following day at noon. The pie is sweet and round; during its preparation, the baker has taken care to hide a coin in the dough (the so-called gold coin). Therefore, during the cutting and distributing of pieces, one of the assembled people will get the coin and be the lucky one of the starting year. The cutting of the vasilopita has survived for many centuries – since ancient Greece, when (likewise) people distributed the celebratory bread. This took place in big rural feasts, such as the Thalysia and the Thesmophoria.

The finikia (another name for melomakarona) are by far the most beloved Greek Christmas sweet; at this point, let me inform those of you who live abroad and haven’t tasted them yet that it is super healthy because it is made by olive oil, semolina, honey, cinnamon, orange and walnuts. It comes to us from Asia Minor: there, people used to decorate their famous finikia by carving on their surface with a thin pair of tweezers. These days, you will find them in all kinds of variations; the most famous of which is covered with bitter or milk chocolate.

The kourabies is the snowy from caster sugar holiday sweet, made of fresh butter and almonds. It also comes from Asia Minor and the name comes from the word kurabyie (meaning crispy double-baked biscuit). Traditionally, it is the first sweet you will be offered to feel welcomed at a house; and, once you’ve tasted it, it’s hard to stick to one!

Finally, the honeyed diples come to complete the sweet Christmas scenery. They come from the Peloponnese; this is a crispy sweet made of thin pastry in pretty shapes that are dipped in honey and sprinkled with ground walnuts.

The stuffed turkey and the slaughtering of the hog

The turkey, stuffed with chestnuts, raisins, and pine nuts, is one of the most popular dishes you can taste at the Christmas table. In truth, of course, the custom is imported from other regions of Europe, where they used to cook pheasant, goose, turkey and peacocks for the festivities.

A more Greek custom is the slaughtering of the hog (otherwise called γουρουνοχαρά, meaning hog-joy), that traces its roots back to ancient Greece; at the time, the process had a cathartic or purgatorial character – like a sacrifice for the gods. Therefore, in Greece, before adopting the turkey custom, we had the slaughtering of the hog. The hog was bred at home throughout the year and, during the festive season, families would gather at each others’ home successively and slaughter one hog per day. The process took special care, as did the roasting, which was succeeded by an endless feast. Today, the custom is still alive in Icaria, as well as certain parts of Thessaly.

The breaking of the pomegranate and the podariko

The breaking of the pomegranate is a custom born in the Peloponnese and spread throughout Greece. In the past, people observed it almost religiously (especially in the province) because they thought it brought money and luck; however, today, it is not so popular. According to the custom, on New Year’s Day, after going to church and before entering the house, the owner of the house should take a pomegranate out of their pocket and break it by throwing it on the ground. Entering the house should be done right foot first; while, when the pomegranate is broken, they should utter the wish out loud: “May the new year be full of health, happiness and joy; and may our pockets be full of gold coins – as many as the seeds of the pomegranate!”

The podariko, on the other hand, is a custom observed to this day and has a symbolic meaning, as it is believed to bring luck, happiness and wealth to the owners of the house. Thus, the first person to visit the house after the change of the year and utter their wishes is the one to make the podariko. Upon the visitor’s entry to the house, the lady of the house should offer coffee and sweets if she wants the wishes to come true; the sweet on offer is usually spoon sweet (most often, quince). Even to this day, in many parts of Greece, the owners of the house ask beforehand a young child (a boy, if the house if full of girls – or vice-versa) to perform the podariko; the logic behind this is that a child’s wishes are innocent – free of envy or cunning.

The hanging of the socks

Traditionally, (in contrast to most other countries) here in Greece, Santa Claus does not visit us on Christmas Eve but on New Year’s Eve! Therefore, all children, having sent him a letter with their desires, proceed to hang empty socks with name tags above the fireplace; so that, when entering from the chimney, the saint can fill them with candy, chocolate and money. If the house does not have a fireplace, like in the old days, the place of the Christmas socks are on the Christmas tree; and so the saint will leave the rest of the presents below the tree on New Year’s Eve.

Τhe kallikantzaroi

The kallikantzaroi are a very old tradition here in Greece; and, in various regions of the country, at this time of year, many particular customs connected to them are revived. There are innumerable legends (both spoken and written) about them, some of which constitute childhood memories, since the stories our grandmothers told us during this time of year were indubitably full of these strange creatures of nature.

So, according to tradition, these tiny malevolent ugly goblins show up every Christmas and run around the house all night, causing trouble and stealing sweets, wine and fruit. Afterword, their mischief complete, they start singing and dancing madly, causing little children to be afraid to leave the house. The kallikantzaroi, who dwell in the depths of the earth all year long, seize the opportunity to surface and wreak havoc during the twelve days of Christmas (December 25th to January 6th) – that is, between the birth of Christ (Christmas) and his baptism and the consecration of the waters (Epiphany/Theophany) – before they return underground. Tradition claims that they are vicious creatures and wish to cause harm upon surfacing; however, they are considered to be so frivolous and silly that they just make minor mischief, without causing serious trouble to the house.

In any event, this story is enough to keep young children in bed and well-behaved during the night for the entire festive season; if nothing more, they too have plenty of time for mischief, since they are free of school and homework!

Feeding the faucet

This is a beautiful Greek custom of older times that is rarely revived today – except perhaps in some villages of Central Greece. According to tradition, on Christmas Eve, girls are supposed (full of piety, of course) to go to the faucet of a spring and fill clay pitchers with water. Before they do that, they should rub the faucet with butter and honey: thus “feeding the faucet”. The “feeding” was performed in order for happiness to flow like water in their home and their lives to be sweet like honey. During the time of observing this custom, girls were supposed to remain silent; this is where the phrase “drank the silent water” (an analogy of the English “the cat got your tongue”) comes from – one that we still use today.

Fragrant colognes

This is a fragrant custom that comes from the Ionian Islands but was loved and adopted in many other regions of Greece. According to this particular tradition, on New Year’s Eve, every youth goes out in the street carrying bottles of cologne, where they sprinkle each other while exchanging the phrase “good severance”, which means “May you joyously part with the old year and happily embrace the new one”.

Epilogue

Countless are the beautiful customs and traditions of our country for the festive season; special and unique their variations in its different regions. You can just get a taste through this article because, in reality, we would need to write many books to include them all! Hoping that I helped you travel mentally and that I got you (even a tiny bit) into the Christmas spirit (despite the difficulty caused by external financial and political circumstances), I will close this article with the wishes of all Beauty Guards and the Appendix with carols that I promised you!

“Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to you all! May this year’s holidays be essential and true; and our hearts be full of love, solidarity and compassion!”

Dimitris Valelis

Appendix:

Christmas Carol / Τα κάλαντα των Χριστουγέννων

Καλήν εσπέραν άρχοντες αν είναι ο ορισμός σας

Χριστού τη θεία γέννηση, να πω στ’ αρχοντικό σας.

«Χριστός γεννάται σήμερον εν Βηθλεέμ τη πόλη

Οι ουρανοί αγάλλονται, χαίρε η φύσις όλη.

Εν τω σπηλαίω τίκτεται, εν φάτνη των αλόγων

Κι ο Βασιλεύς των Ουρανών κι ο Ποιητής των όλων.

Πλήθος αγγέλων ψάλλουσι το «Δόξα εν Υψίστοις»

Και τούτο άξιον εστί η των ποιμένων πίστις.

Εκ της Περσίας έρχονται τρεις μάγοι με τα δώρα

Άστρον λαμπρόν τους οδηγεί χωρίς να λείψει ώρα.

Φθάσαντες εις Ιερουσαλήμ με πόθον ερωτώσι

Που εγεννήθη ο Χριστός να πα’ να τον ευρώσι.

Δια Χριστόν ως ήκουσε ο βασιλεύς Ηρώδης

Αμέσως εταράχθηκε κι έγινε θηριώδης,

Ότι πολύ φοβήθηκε δια την βασιλείαν

Μη του την πάρει ο Χριστός και χάσει την αξίαν.

Κράζει τους μάγους και ρωτά που ο Χριστός γεννάται

Της Βηθλεέμ ηκούσθηκε, ως η γραφή διηγάται.»

Σε αυτό το σπίτι που’ ρθαμε, πέτρα να μη ραγίσει

Κι ο νοικοκύρης του σπιτιού, χίλια χρόνια να ζήσει

New Year’s Eve Carol / Τα κάλαντα της Πρωτοχρονιάς

Αρχιμηνιά και αρχιχρονιά

Ψηλή μου δεντρολιβανιά

Κι αρχή καλός μας χρόνος

Εκκλησιά με τα’ άγιο θρόνο.

Αρχή που βγήκε ο Χριστός

Άγιος και πνευματικός

Στη γη να περπατήσει

Και να μας καλοκαρδίσει

Άγιος Βασίλης έρχεται

Και δεν μας καταδέχεται

Από την Καισαρεία

Συ’ σαι αρχόντισσα κυρία.

Βαστά εικόνα και χαρτί

Ζαχαροκάντιο ζυμωτή

Χαρτί και καλαμάρι

Δες και με το παλικάρι.

Το καλαμάρι έγραφε

Τη μοίρα του την έλεγε

Και το χαρτί ομίλει

Άγιε μου, Άγιε Βασίλη!

Κάτσε να φας, κάτσε να πιεις

Κάτσε τον πόνο σου να πεις

Κάτσε, κάτσε να τραγουδήσεις

Και να μας- και να μας καλοκαρδίσεις!

Epiphany/Theophany Carol / Τα κάλαντα των Φώτων

Σήμερα τοα φώτα κι ο φωτισμός

Η χαρά μεγάλη κι ο αγιασμός

Κάτω στον Ιορδάνη τον πόταμο

Κάθετ’ η κυρά μας η Παναγιά

Σπάργανα βαστάει, κερί κρατεί

Και τον Αη Γιάννη παρακαλεί:

-Άγιε μου Αη Γιάννη και βαπτιστή

Δύνασαι βαπτίσεις Θεού παιδί;

-Δύναμαι και θέλω και προσκυνώ

Και τον Κύριο μου παρακαλώ

Να ανέβω πάνω στον Ουρανό

Να μαζέψω ρόδα και λίβανο.

-Άγιε μου Αη Γιάννη και Βαπτιστή

Έλα να βαπτίσεις Θεού παιδί

Ν’ αγιαστούν οι κάμποι και τα νερά

Ν’ αγιαστεί κι ο αφέντης με την κυρά.

Σφάξαμε τον πετεινό, είδαμε τα φώτα

Δώστε μας το μπαξίσι μας, να πάμε σ’ άλλη πόρτα!