Having heard many of my female friends complaining that their partner is a “mommy’s boy”, I sought the causes of this situation; a situation that, in Greece, has pandemic dimensions, despite the illusion of a progressive society (supported by the latest smartphones).

Today’s mothers, having been born between the 1940s and the 1970s (thus between the ages of 45 and 75), essentially belong to the first post-war generation of this country. A generation that grew up lacking many things but that also had the chance to see life improve through hard work. So, when the members of this generation had children, they decreed that their children would want for nothing and have a good life – this meant, as a rule, the straightforward course of good education – good marriage – children.

For this purpose, trillions of drachmas and euros were invested in the native industries of private tutoring, of kebab shops (in cities with universities), and marriages. Millions of apartments housed the dream of a better life in the city. Countless master’s degrees served to prolong ambitions and unemployment numbers. Hundreds of members of parliament built a career taking care that “the child doesn’t have to serve in the army far from home” and making sure that “the child has a stable job (in the public sector)”.

And here comes the orange juice every morning when the child is studying for the exams. And the sarma every Sunday. And the first car as a gift on graduation. And this is how the offspring of the first post-war generation, now young adults and middle-aged, learned that everything is provided and ready. They learned that they will always have money – even though they believe that the job they are worth is beneath them and they shouldn’t bother. They learned that they can always rely on the Holy Greek Family – be it grandma’s pension or mommy’s savings – to pay for the car insurance or for that long weekend in Rome with their partner, which they always dreamed of.

But, even though all of the above were just a piece of the provider’s mentality (who works to bring home the money and secure a better life for his children) that characterized the Greek father, for the Greek mother things were much more complicated. Living with a husband who (even if he wasn’t inflicted on her by an arranged marriage was hardly ever present) was, as a rule, neither sentimental nor exactly expressive, she transferred all her expectations for emotional support to her male children. These fateful sons of the golden age of Nutella were (consciously or unconsciously) systematically castrated in advance, in order for the insecure Greek mother (“who sacrificed everything”) not to lack the appropriate terrain on which to exercise the cunning power of pastitsio.

And since it’s very rare to deny being looked after and rebuff unconditional affection, the sentimental enslavement of these sons took place before they knew it was happening. Suddenly, every development in their personal lives became a topic for discussion for the family convention with all members present – i.e., both mother and son. The father, if he’s not at the local cafe or playing backgammon with his friends, doesn’t like the phone that much. But the Greek mother is like the Duracell bunny. She will employ all means available in order to manipulate:

- Provocation of self-pity (“I have a bad heart, what do you want, to kill me with this tramp you want to bring into our house?”)

- Provocation of pity to a third party (“Your father didn’t waste his life working on a ship/on a building site/in a bar/in the fields so that this tart can prance around our house and not let us see you” or “Auntie Toula will not survive this wedding – not after auntie Gelly died”, etc.)

- Buying of conscience (“Drop her, sweetheart, and never you mind – I’ll buy you that bike you want”)

- Projection with an essence of occupation syndrome (“But you don’t even like her, I can see it, you’re not happy, you’ve lost weight – she’s not feeding you properly”)

- Direct comparison (“Matoula’s son married a teacher and you’re going to marry an actress?”)

- Covert belittlement with a metaphysical dimension (“She’s wrapped you around her little finger with those tricks of hers; she must have put a spell on you”)

- Distraction/diversion (“Your brother is studying for his degree now; do you want to upset him?”)

- Calling on culinary customs (“Does she know how to do kapamas like I do? Of course not! You two always eat out!”)

- Biological expertise (“She’s so thin by spending all her time at the gym; how is she going to have children?”)

- Internalization of social outcry (“What will Panagoula who lives across the street/auntie Betty/your godmother/the priest say?”)

In short, any bridal candidate who doesn’t fulfill the model of post-junta perfection (pretty but not that much, mute, with a bit of an education, with a dowry and looks into the eyes of the precious male offspring adoringly) is elevated to the sphere of an Armageddon-like enemy; one who wishes to grab the innocent son from the affectionate arms of his destitute mother.

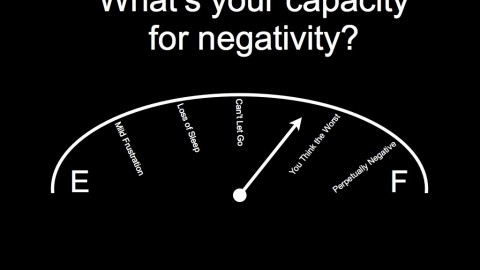

This mother model – authoritarian, insecure, egocentric, smug, theatrical, dramatic, Almodovar-esque, yet so vivid around us – continues to castrate men, thus worsening the relationship crisis, and drives women away from ready-made grooms with PhDs and straight into the arms of “bad boys”, where they seek the missing thrill. And this is where trouble starts. Because from one extreme type of man, who looks at you through the eyes of his mother, you go to the vagabond from the problematic family, who lives for today and will readily hurt you – just like he was hurt as a child by his parents’ indifference.

Is there a golden ratio between those two negative motifs? Obviously. Are there men who have a healthy amount of respect for their family without being manipulated by it? Of course. Is it just those whose mother has died? No. How to distinguish them? The following indications might help:

- They are financially and geographically independent (those living in the attic of their parents’ house are excluded – no matter how trendy the attic is).

- They are not in love with the telephone.

- They can cook.

- They don’t use the word “mommy”; instead, they say “my mother/my mom”.

- They don’t mention their mother more than once a week.

In closing (jokes aside), a reminder: everyone can better their character, should they really want to. To this direction, they will need their friends’ discreet assistance.

current_Panos